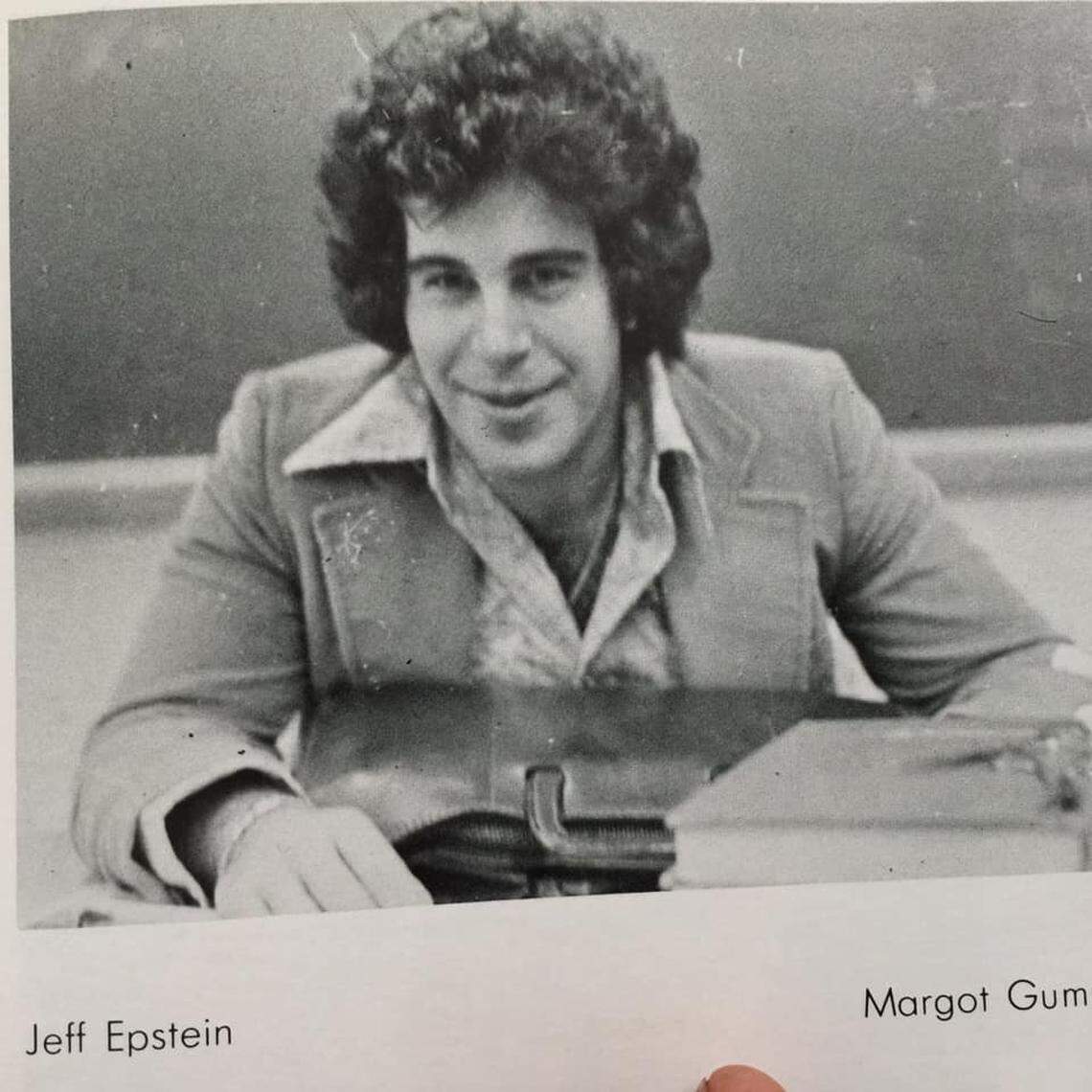

Jeffrey Epstein in the 1980s: The Decade Where the Story Stops Making Sense

A Career That Should Have Ended but Didn’t

When Jeffrey Epstein left Bear Stearns in 1981, he did so without a college degree, without an independent client base, and without a visible track record that would normally sustain a Wall Street career. In that era, finance was rigidly credentialed and reputation driven. So how did a man in that position not only survive but reappear advising billionaires? Who vouched for him when the normal markers of credibility were missing? What networks allowed him to reenter elite finance without the résumé typically required?

The Early 1980s Silence

Public documentation of Epstein’s activities in the early 1980s is sparse. He did not launch a public hedge fund, did not advertise investment strategies, and did not cultivate a visible investor base. Yet he clearly was building relationships. If money and access were already moving toward him, what mechanisms made that possible? Was he offering specialized tax or offshore structuring knowledge that wealthy clients valued, or was he being introduced into circles that operate largely outside public scrutiny? The absence of records does not prove wrongdoing, but it raises the investigative question of why a figure who later proved so influential left so little trace at this stage.

The Leslie Wexner Breakthrough

Epstein’s rise in the 1980s becomes tangible only when he connects with Leslie Wexner, founder of The Limited and one of the richest retail figures in the United States. By the late 1980s Epstein was advising Wexner personally and handling elements of his financial world. This is where the story becomes difficult to explain conventionally. Why would a billionaire with access to top global financial firms place extraordinary trust in someone without a degree or a visible investment track record? What specific skill or introduction convinced Wexner to elevate Epstein so rapidly? Was it financial expertise, personal rapport, or the influence of mutual intermediaries who remain largely unnamed in public reporting?

Wexner’s Philanthropy and Israel Connections

Wexner founded the Wexner Foundation in 1983, focusing heavily on Jewish leadership development in North America and Israel. Over time the foundation funded programs for Israeli public officials and supported fellowships tied to Harvard’s Kennedy School. These activities are openly documented and not controversial in themselves. The investigative issue is Epstein’s proximity to this philanthropic infrastructure. If Epstein gained influence over Wexner’s financial affairs, how much insight did he have into these international philanthropic flows? Did his advisory role extend into strategic decisions about where money moved, or was he strictly a technical financial manager? The fact that his authority grew in parallel with Wexner’s expanding global philanthropic footprint naturally raises questions about how intertwined those roles became.

The Mansion and the Level of Trust

In 1989 Wexner purchased the Manhattan townhouse on East 71st Street, and Epstein became its occupant. Advisers rarely live in property bought by clients. What does that arrangement say about the level of personal trust Epstein commanded? Did this reflect loyalty, dependency, or a broader partnership that has never been fully explained? If Epstein’s role was purely financial, why was the relationship expressed through such an extraordinary personal gesture?

Black Monday and Epstein’s Position

When markets collapsed in October 1987, many major financiers were scrutinized, interviewed, or exposed. Epstein remained largely absent from public reporting about the crash. Was that because he truly had no major market exposure, or because he was operating in private wealth channels insulated from institutional markets? If he was advising billionaires during that time, how did the crash affect their assets and strategies, and what role did he play in navigating that moment? The lack of clear answers makes his silence during one of the decade’s defining financial events itself noteworthy.

Intelligence Speculation and Structural Questions

There is no declassified document proving Epstein worked for any intelligence agency in the 1980s. That must be stated clearly. But his ascent still challenges conventional explanations. When someone gains extraordinary access without conventional credentials, speculation about hidden backing becomes inevitable. The responsible investigative question is not whether one specific agency was involved, but what structural forces enabled his rise. Was Epstein simply an unusually persuasive financial strategist, or did he benefit from networks that operate beyond public financial systems? Why did his authority expand so rapidly while his public record remained so thin?

What the 1980s Actually Built

By the end of the decade Epstein had achieved proximity to billionaire wealth, founded a private advisory firm claiming to serve only the ultra rich, and positioned himself inside networks intersecting finance, philanthropy, and international leadership development. He was not yet famous, but he was insulated. From my point of view, that insulation is the real story. The 1980s created the structures of access and trust that later made him difficult to challenge.

The Core Question

If this series aims to understand Epstein rather than simply recount his later crimes, the key question begins here. Who granted him access, what convinced them, and why did his authority grow despite the absence of conventional credentials? The 1980s are where those questions originate, and until they are answered, the foundation of Epstein’s power remains unresolved.

More

more

like this

like this

On this blog, I write about what I love: AI, web design, graphic design, SEO, tech, and cinema, with a personal twist.